Boards are responsible for responding to and preventing sexual misconduct. When that’s not clear, difficulties will arise. We hope other sanghas won’t have to learn this firsthand as we did. Here is what we would like other sanghas, and especially other boards, to know about the board’s role:

What it means to be a nonprofit

Founder syndrome and puppet boards

Legal and ethical duties of a board

Boards and sexual misconduct

The (ir)relevance of lawsuits

Pushback

Differences between board power and clergy power

Shared leadership

An offer of mutual support

What it means to be a nonprofit

Many Buddhist communities in the U.S. begin informally, with a group of people deciding to meet regularly in a living room, in some other borrowed space, or over the internet. The question “Who’s in charge here?” might be answered, “Oh, there’s not much to decide” or “All of us—we do everything by consensus.” If the group was founded by a teacher, the answer might instead be, “Of course it’s the teacher who’s in charge; after all, this is their group.”

Incorporating as a nonprofit changes things in ways that are easy to underestimate. Becoming a nonprofit is not just a matter of making donations tax-deductible. Once a group has become a nonprofit, it is a legal entity in its own right, separate from its founders. This new legal entity is bound by legal documents (the articles of incorporation and bylaws), and the question “Who’s in charge here?” is definitively settled: a nonprofit governs itself, via its board of directors.

This is true regardless of the mission of the nonprofit. There is no special exemption for nonprofits founded by spiritual teachers. Once an organization has been incorporated as a nonprofit, it is a different organization: it is an organization run by a board and not by founders or teachers. If this change is glossed over or trivialized, it is a major warning sign for future problems.

Founder syndrome and puppet boards

Founder syndrome can affect any organization, whether for-profit or nonprofit. Wikipedia defines founder syndrome as “the difficulty faced by organizations…where one or more founders maintain disproportionate power and influence following the effective initial establishment of the organization, leading to a wide range of problems.”

Founder syndrome is a predictable growing pain. It is not easy for founders to let go of the power they initially exercised, even if they are enthusiastic about incorporating as a nonprofit (which by definition requires them to relinquish power to the board). Nor is it easy for nonprofit board members to exercise the power they actually hold (and must hold) if it means overriding the preferences of a founder—particularly if that founder is also their teacher.

What does founder syndrome look like? Having founders or spiritual teachers serving as board members is not necessarily a problem, as long as they don’t expect to have “disproportionate power and influence.” It is a problem, though, if other board members think of themselves as a de facto staff and the founders as their de facto bosses. Founder syndrome can also be seen when, in times of urgency or crisis, the board is pressured to fast-track decisions in line with the founder’s wishes. Founder syndrome can be written into an organization’s bylaws through attempts to create a lifetime board appointment for the founder or clauses to make it more difficult to remove a director who is a founder than it is to remove other directors. Founder syndrome can take place even after the founder has left the organization if, for instance, there is pressure to give a transgressing teacher inappropriate latitude because of their status as the founder.

In the worst case scenario, the boards become “puppets” of the founder, relegated to merely adding their stamp of approval on decisions already made.

Puppet boards are bad for organizations and for their directors. Organizations with puppet boards suffer because they lack transparent, independent leadership. Directors suffer because serving on a puppet board puts them at risk of violating their legal and ethical duties as fiduciaries of the organization.

Legal and ethical duties of a board

What does it mean for board members to be fiduciaries of the organization? Many people misunderstand the word “fiduciary,” thinking it just means “something to do with money.” This misunderstanding pairs easily with a “puppet board” concept of board duties: perhaps a board is just supposed to manage an organization’s finances (taking in donations, paying the rent), leaving all other decisions to the organization’s real leaders; that is, to its founder(s) and/or—in the case of Buddhist organizations—its teachers.

The truth is the opposite. Being a fiduciary means being entrusted with accountability for an organization’s well-being. It means taking on the highest possible standard of care under the law. It’s a big responsibility. As fiduciaries, board members promise to act on behalf of the organization they serve. They must determine, as best they can and using their own judgment, what is in the best interests of their organization across every dimension (not just finance), and then they must act in those best interests, no matter what kind of pushback they encounter.

Board members’ fiduciary duty is often broken down into three overlapping aspects: the duty of obedience requires them to follow the law and carry out the organization’s stated mission; the duty of loyalty requires them to place the organization’s interests above their own at all times; and the duty of care requires them to take their board duties seriously: they need to be active, not passive, in looking out for the organization’s interests.

Boards and sexual misconduct

Board members’ duty of care requires them to take active steps to try to prevent sexual misconduct from occurring. This is not a matter of ensuring that there are “no bad apples” among the teachers. Sexual misconduct is not a “bad apple” kind of problem; it is a systemic risk that demands systemic solutions.

What might systemic solutions look like? This is a question boards should ask themselves continuously since there’s always room for improvement. Among other things, boards should consider these preventative measures:

- Giving teachers ongoing access to relevant training, such as the Buddhist Healthy Boundaries course;

- Providing regular training to sangha members on teacher-student boundaries, ethics, non-profit structure, and related matters;

- Adopting clear and detailed bylaws and governance policies, including ethics policies and procedures;

- Empowering an ethics council to work on education and prevention and recruiting an ethics ombudsperson to help with remediation;

- Ensuring that students have clear channels to seek information and assistance; and

- Offering support for teachers and students around “personal shadow.”

Of course, boards must also take effective corrective action if sexual misconduct occurs. This could include:

- Offering support to the victim;

- Conducting an investigation, using outside providers as necessary;

- Reporting the matter to arguably relevant external bodies such as the SZBA (which has a reporting clause in its ethics statement) or the AZTA;

- Imposing any necessary sanctions, restrictions, or path-to-recovery requirements on the transgressor; and

- Sharing information as transparently as possible with the sangha.

Note: Despite what these two separate sets of bullet points might suggest, the distinction between prevention and correction is not a sharp one. In fact, studies show that taking effective corrective action when sexual misconduct occurs may be, in itself, the most powerful form of prevention.

Also, a caution regarding requirements for a path to recovery: members of an injured community may be eager to recognize any movement toward regret on behalf of the transgressor as sufficient for reinstatement or absolution. The board must bear in mind that prior to reinstatement, a transgressor must demonstrate true rehabilitation through following a suite of actions, such as those recommended by the FaithTrust Institute, bulleted below. Resistance to these steps on the part of the transgressor often indicates a resistance to the gravity of what they’ve done:

- Express and demonstrate true remorse;

- Take full responsibility;

- Step down from teaching [or similar roles] until restitution work is done;

- Notify professional organizations;

- Engage in therapy with a counselor who specializes in clergy abuse/professional misconduct;

- Submit (vetted) written apologies;

- Submit reports by teacher and therapist to board; and (only then)

- Apply for reinstatement.

Note: If a transgressor does apply for reinstatement, it is important to consult with the student (or students) harmed in order to center their needs.

The (ir)relevance of lawsuits

Sometimes people recognize that boards are responsible for responding to and trying to prevent sexual misconduct but mischaracterize the basis of that responsibility as being grounded in the need for the organization to “avoid expensive lawsuits.”

Of course, all other things being equal, it is in an organization’s best interest to avoid being sued, and board members should do what they can to act on that interest. However, it is a mistake to focus on this outcome rather than on the organization’s core interests. The board of a sangha should focus on preventing and correcting sexual misconduct not to keep the organization from being sued (or from being sued themselves, in their capacity as directors), but rather because doing so will make the sangha a safe (or at least safer) place for Buddhist practice. The shorter slogan might be: just do the right thing so that your sangha can carry out its mission.

The FaithTrust Institute makes a similar distinction between an “Institutional Protection Agenda,” which prioritizes defending the organization in civil litigation, and a “Justice-Making Agenda,” which prioritizes restitution for survivors and prevention training. Even those labels can be confusing, though, since protection of the institution’s real interests entails justice-making.

Focusing on doing the right thing rather than avoiding lawsuits at all costs allows board members to prioritize their organization’s core interests. It also sets up the right priorities in cases where the two bases of responsibility conflict. In the case of teacher misconduct, the best thing for the sangha would not be to resist liability at all costs by minimizing or obscuring the harm done, but rather to settle a lawsuit on reasonable terms or otherwise compensate a victim for the harm that they’ve suffered. (How could this be so? Because good corrective action is also good prevention, and because care of victims is part of a board’s duty of care for the sangha, it is not necessarily appropriate for a board to resist a lawsuit at all costs, should one be brought. The correct choice, where the sangha is arguably liable for harms, could be to reach a settlement that makes the victim whole.)

Pushback

To reiterate: in order to carry out their fiduciary duties, board members must try to determine what is in the best interests of their organization and then act in those best interests—and they must do so no matter what kind of pushback they encounter.

Pushback may take the form of the “DARVO” dynamic (short for “Deny, Attack, and Reverse Victim and Offender”), with the board accused of supporting a victim who is the “true” offender, and/or with the board itself in the role of offender (“We wouldn’t have a problem if it weren’t for what the board is doing”). (See below for a more detailed discussion.)

It may take the form of pressure from distraught, confused, or frustrated sangha members, who argue that the board is overreacting, overreaching, or making things worse by “wallowing” in the issue, when in fact the board is simply exercising its duty of care and making space for everyone’s recovery.

It may take the form of pressure from teachers who disagree with board actions and—more fundamentally—dispute the board’s ultimate authority to address sexual misconduct matters. Among other things, teachers who wish, consciously or unconsciously, to undermine board decisions may end up:

- Arguing that the entire board must recuse itself because board members are personally impacted by fallout from the sexual misconduct

(in fact, it is both possible and normal for boards under such circumstances to carry out their duties, and to do so ethically, among other reasons because there simply are no completely unimpacted people ready to step into board roles);

- Arguing that the board should “just hand the whole matter over” to some third party to handle

(in fact, the board must retain ultimate responsibility, given its fiduciary duty to the organization);

- Arguing that “this is a spiritual matter” and that board actions—and especially any reference to the law or legal and ethical duties—somehow corrupts a spiritual solution

(in fact, this is a false dichotomy: board members may well be acting on their highest spiritual aspirations when they try to carry out their duty of care for the sangha);

- Taking systemic preventative measures personally, as if comprehensive ethics policies or teacher training requirements were an insult to “good apple” teachers

(in fact, studies show we are all safer when organizations treat misconduct as a systemic risk rather than an issue of “good” and “bad” teachers); or

- Attempting to control key decisions, such as (1) which outside consultants or providers to work with; (2) whether, when, or how a teacher who has committed sexual misconduct should be invited to speak to the sangha; or (3) whether, when, or how the sangha should publicly discuss any aspect of the misconduct

(in fact, all of these decisions fall under the board’s purview, given board members’ fiduciary duties).

Board members may find these various forms of pushback to be intense and difficult to bear. Serving as a board member can definitely be, to use a common Zen phrase, “a field of practice.” Board members do well to brace themselves, try to stay centered, and rely on each other for support.

Differences between board power and teacher power

What if the alleged victim of a teacher’s sexual misconduct is also a member of the board? This is not an unlikely scenario, given the small size of most sanghas and the large overlap between the most engaged sangha members (who are particularly likely to be exposed to teacher misconduct) and those sangha members who are willing to serve on the board.

Does the power that an individual carries by virtue of being a board member counteract the power dynamics of the teacher-student relationship so that a board member cannot possibly be a victim of clergy misconduct? Or more than that: would misconduct rules actually be reversed under these circumstances so that the burden of boundary-keeping would be on the board member rather than the teacher?

The answer is no, because there are critical differences between board and teacher power. The nature of board leadership does not entail the kind of vulnerability and transference/countertransference as described with teacher roles and is therefore not governed by the civil and criminal laws that clergy and spiritual teachers (as well as therapists, chaplains, and other care providers) are subject to. Thus, misconduct rules would not place the burden of boundary-keeping on the board member rather than the teacher (thereby reversing their roles and making the teacher into a victim). Nor does the type of power exercised by a board member protect them from being vulnerable to a teacher’s abuse of power. Board members may be victimized just like any other member of the sangha.

The only relevance of a victim’s status as a board member is this: per ordinary conflict-of-interest principles as laid out in board bylaws, they must be recused from any board decision making in which they might be seen to have a conflict of interest.

Shared leadership

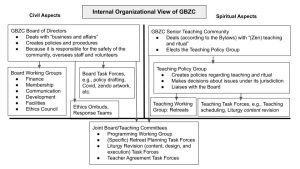

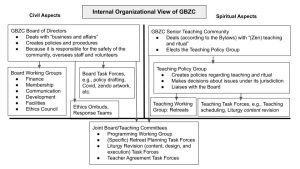

What does an appropriate balance of powers look like in a healthy and resilient sangha? How should the board and teachers share leadership? There is no single prescription, but this chart of GBZC’s newly clarified structure describes one possibility:

It’s important to recognize that this structure still permits input from founders and/or teachers to the board. As noted above, founders or spiritual teachers can even serve as voting board members, as long as they don’t expect to have “disproportionate power and influence.” At GBZC, we’ve decided to strike a prophylactic balance (minimizing the risk of puppet boards) by adding the following provision to our bylaws: “Members of the Senior Teaching Community shall not stand for election as a Director, though a Director who becomes a Senior Teacher may finish their term as a Director.”

Furthermore, founders and/or teachers are always welcome to serve in an ex officio manner on the board (attending regularly and giving input without being voting members). They may also be invited to serve on the ethics response teams that guide the sangha’s response to incidents of sexual misconduct, with the understanding that, by virtue of its fiduciary duties, the board will always hold the ultimate responsibility for decision making related to matters of sexual misconduct.

An offer of mutual support

We noted at the outset that at GBZC, the process of recovering from sexual misconduct was made particularly difficult due to a lack of clarity or assent regarding the board’s role in responding to and preventing misconduct. We hope these materials about power structures and power struggles are helpful to other sanghas and particularly to other boards. If we can provide any further support, please don’t hesitate to contact us at resilientsangha@bostonzen.org.

(last updated 2/27/23)

Next: Sangha Responses to Misconduct: Common Dynamics (DARVO)

Published June 12, 2022