Right Use of PowerTM (RUP) is an approach to ethics that we found significantly damaging to our community. It presented our sangha with a distorted view, positioned outside the mainstream research consensus (see Resource List), about teacher/student boundaries—topics that require rigorous, clear-sighted guidance. In this essay, we outline our concerns with RUP’s modality as it was taught in 2019-21 and how it impacted our sangha at a time of profound crisis, the sexual misconduct of our spiritual director. It is our hope that this narrative will help inform other well-intended sanghas, looking for guidance in ethics, about teachings we found harmful.

Background

According to the RUP webpage, the Right Use of PowerTM paradigm offers “a dynamic, inspiring, and relational approach to the ethical use of power to promote well-being and the common good.” Our community hired Right Use of Power-affiliated professionals on two occasions: In 2019 we hired a trainer (an individual who was also at the time the President of the Soto Zen Buddhist Association) for a Right Use of Power workshop. In 2021 we hired the founder of the Right Use of PowerTM Institute and a colleague as consultants in response to our Spiritual Director’s sexual boundary violation. (In keeping with our commitment to foster dialogue that leads to healthier Buddhist sanghas, we foreground systems and paradigms as the subject of our critique, and thus refer to roles and not people.)

Summary

In painful retrospect, we’ve come to see the extent of harm we feel was inflicted on our community both by the training and the consulting aspects of RUP, in the following regards:

- The training we received in 2019 did not prepare us for sexual misconduct by a teacher. In fact, the content of the training made it more difficult to respond appropriately to sexual misconduct, requiring sangha members to unlearn some of the key content we’d been taught in order to take compassionate action.

- The consultants we hired in 2021 replicated and reinforced abuser dynamics in their interactions with the survivor, and instructed our sangha members and teachers to do the same.

About the consultants’ work with our community, the survivor of the sexual misconduct writes, “The Right Use of Power consultants worked against my currents of understanding, insight, intuition, and felt response; indeed, their process represented a continuation of my teacher/counselor’s abuse on almost every psychological and spiritual level.”

We have tried to engage with the trainer and consultants about the impacts of their interventions and areas for improvement, but have not been met with receptivity to feedback. We stand ready and willing to work with them on improvements to their program, when they are ready to engage.

It is almost unfathomable that those who purport to be experts in responding to sexual misconduct would actually deepen the harm. This reality deserves deep investigation. That they would be held in such high esteem within the greater Buddhist community deserves action. We cannot un-hire the trainer or consultants, but we can alert other sanghas to the difficult path we’ve tread. So that others can benefit from our painfully earned insights and find a safer path to healing, we are sharing at length our concerns with the Right Use of PowerTM modality and its consulting arm.

Deficiencies of Right Use of Power Training as Prevention

The training in the RUP program that we received in 2019 was, in our view, dangerous both in what it taught and in what it left out.

At its heart, the program had a preoccupation with listing and classifying types of power, the primary of which are role, status and personal power. Upon first encounter, differentiating these types of power appears to be merely a ratification of the obvious: just because a spiritual teacher is in a position of power (a combination of “role” and “status” power), that doesn’t mean they can steal a student’s inherent power (“personal” power or the other kinds of role/status powers a student may possess). What we saw in our community, however, is that this framing laid the groundwork for the notion that victims always bear some measure of responsibility: since they never relinquish the other “kinds” of power they possess, they are in effect always co-responsible for their abuse.

This isn’t merely a theoretical implication of RUP’s power taxonomy: in 2021, the trainer sent an email to the President and Vice President of the GBZC board sharing her view that the student who was abused at our center had also mis-used her power and that the student should apologize to her abuser’s wife. This guidance, seemingly inexplicable for a trainer in ethics, was actually coherent given the training they had given our sangha. It was a vivid demonstration of our experience of the broken foundations of the RUP approach.

Here are highlighted concerns of our experience with RUP as prevention:

- The program taught that the person in the up-power position is “150% responsible for good relations and conditions” while the person in the down-power position is “100% responsible for good relationships and conditions, and for resolving problems and conflicts.” This formulation of teacher/student responsibility in the context of sexual misconduct is victim-blaming. Research on clergy and therapist abuse, and policies of major counseling and religious organizations, recognize that the person in the low-power position is being exploited (see Resource List). Abuse of spiritual and/or emotional power is 100% on the person in the high-power position, 0% on the person abused. In the words of the survivor in our community, “Right Use of Power’s abstract math of 150/100 only aided in the smoke screening and perpetuating of abuse.”

- In addition, the slides presented at the training said that the goal is assuring “well-being for both teacher and student.” Yet the teacher, in offering themself as a trusted spiritual guide, is (like other client-serving professionals such as therapists and lawyers) promising, as a matter of professional ethics, to make the student’s well-being the goal of the relationship, not just “a” goal on a co-equal standing with improving their own well-being.

- The program also left out very important preventative measures. In a much later post-misconduct training for our community, Jan Chozen Bays (currently with Buddhist Healthy Boundaries) presented a simple list of “red flags,” including private communications, private meeting spaces; special attention, advancement, gifts or favors; secrecy (demands for). None of these are included in the RUP slides. (Warnings about private meetings, special attention, and demands for secrecy may have helped in our case, as they were all very much a part of the abuse.)

- Lastly, to the extent this preventative program tries to prepare communities to deal with abuses of power should they occur, the training we received was inadequate. Our training presented the idea that the individual who caused injury should come to a personal decision to offer a sincere apology and make amends. There was no mention of the legal responsibility of clergy to maintain appropriate boundaries, nor of the legal “duty of care” that non-profit boards have, which includes dealing with misconduct by staff or volunteers. Nor was there any hint that, according to research, clergy rehabilitation is a process that requires expert help and may take years, if successful at all—not something to be left to an individual to decide for themself. And, lastly, there was no mention of the fact that the teacher’s idea of “amends” may not correspond to the needs of the person abused or of the community.

Deficiencies of RUP-Associated Consulting for Addressing the Consequences

In late 2020, upon the advice of the trainer, the GBZC board hired the founder of the Right Use of Power Institute and the author of the self-published Right Use of Power: The Heart of Ethics to give us initial advice about how to respond to our Spiritual Director’s misconduct. A month or so later, in early 2021, we entered a separate agreement to hire both the author and one of their colleagues to conduct a longer process involving the whole sangha—a decision that almost tore the board apart, as some board members could anticipate the failings of the consultants’ approach. If you look at the Right Use of PowerTM website, it is clear that their primary focus is training. However, RUP also offers consulting. The second consultant, listed as part of the RUP “core faculty,” has long been affiliated with the Right Use of Power Institute, and has their own consulting business built around “restorative practices.” While what the two consultants delivered was a mix of RUP principles and the second consultant’s “restorative practices,” and not just what corresponded to the RUP training, the written contract was explicitly between RUP and our community.

Because the abuser in our situation admitted the basic facts of his sexual misconduct, the consultants seemed to have mistakenly presumed that he was fully repentant and ready to engage directly with the student he had abused. (The consultants appeared to express no curiosity about whether or not this was appropriate for the student). As they facilitated interactions between survivor and transgressor, both directly or as go-betweens, the consultants came across as attempting to control the survivor’s engagement in order for the survivor to be compliant with their vision for the process. This control included attempting to censor the survivor’s narrative of events, asking her to center the abuser’s needs over her own, and requiring the survivor to keep the abuser’s mediated interactions with her confidential. Again, these demands mirrored the demands the abuser made of the survivor during the year-long tenure of his abuse.

Here are the highlighted concerns we experienced with RUP as crisis respondent:

- The consultants demonstrated what we believe was a deficient understanding of the issue of consent in a case of clergy abuse of power. Some weeks after the disclosure of misconduct, the board sent out a “FAQ & Resource List” to the sangha, including materials about the impossibility of consent in a teacher-student context. The consultants wrote that this resource “could be confusing to community members about the seriousness of [the teacher’s] misuse of power,” worrying that it could “possibly inaccurately escalat[e] perceptions of what might have happened.” Yet lack of consent is the core issue in the case of clergy abuse; it is the reason the behavior is considered illegal under both civil and criminal law, and it is the reality sanghas must turn toward if they are to appropriately prevent or respond to cases of abuse. Their deficient understanding was further illustrated by their insistence that communications to the sangha should use the soft-pedaling and inaccurate phrase “secret romantic relationship” rather than “abuse.”

- The consultants’ “restorative process” approach drew explicitly on the better-known Restorative Justice literature, while—at least as we saw applied in our case—dangerously distorting that notion. What these consultants offered was totally inappropriate for a case of extremely recent abuse in which spiritual and psychological healing had not even begun. Restorative Justice is a well-established process that can only take place under very specific circumstances—none of which were present here. It typically takes years (not weeks) for an offender to be ready to enter into a restorative justice process; among other things, the offender needs to be ready to wholly accept their own status as “offender” and the status of the other party as “victim” (see letter from Kara Hayes, explaining necessity of language the consultants rejected). An authentic restorative justice process requires that the mediators determine that “the victim will not be further harmed by the meeting with the offender” (source) and that the offender, in a sincere apology, will be willing to “ced[e] to the victim…control and power” (source). In our community, the teacher attempted to gaslight the student even in their very first mediated session facilitated by these consultants. (While, we believe, taking on this consulting job was wrong from the beginning, the RUP consultants should certainly have realized their mistake at this point and withdrawn.)

- The consultants treated sexual misconduct in the same framing one might use for a collegial misunderstanding or an argument between spouses. Thus, the survivor was submitted to a rote formula they deployed for conflict (misnamed “restorative justice,” see bullet above) which included a culminating hours-long sharing circle where representatives of affected parties spoke in a series of semi-rehearsed interactions, including a round of gratitude-sharing for and about the perpetrator. According to the survivor, “It was me who had to suggest to [the consultants] that I not be part of the ‘gratitude circle’ they’d plan to hold at the reparative circle for everyone to thank my abuser for his teaching. So much of the dynamic between me and the teacher had been based on my gratitude for his teaching. That was the very thing indeed that had become warped and utilized for abuse. It was me who had to say to our consultants that I would not participate in that part of the circle.” The survivor further elaborates, “They thought it would ease his shame to hear all the good people had gotten from him, but they did not ask me about its potential impact on me, whether or not I felt my own shame or a demoralizing lack of spiritual confidence after this experience, worried how people would see me, etc. I was pretty invisible to the whole process to [the consultants] except as a caricature of ‘the student.’” In fact, the only actionable item coming out of the three-hour session was an item that the transgressor’s support person demanded at his request – a “ceremony of apology” before the sangha for the transgressor that the survivor did not attend out of protest.

- Their process focused disproportionately on the teacher’s desires while neglecting the student’s needs. The student was exposed to further harm in the form of exceedingly premature “mediation” sessions with the teacher while she was still reeling from the spiritual and emotional abuse. Their model did not include the student having a support person at these meetings, and the student was told that she should keep them confidential–including anything her abuser shared, replicating the dynamic of secrecy he had required of her. She reports that in response to her detailed communication to these consultants about how the teacher’s account (during these sessions) did not accord with her experience, they told her, “This is not a time for facts, gathering evidence, or shaming and blaming.” According to the student, the consultants’ “focus on ‘subjective narrative’ over ‘truth’ or ‘facts’ allowed a continued manipulation of the narrative by my abuser, which had been part of the abuse all along. It further confused me. It’s like knowing something is deeply wrong but not even having words for it. Overall, their process thickened the fog, created more fog, and did not cut through to compassion or wisdom for me and nor for, I imagine, anyone else.”

- The RUP consultants further isolated and undermined the student and downplayed the facts of the abuse by encouraging the board and senior teachers to take a position of “neutrality,” not seek to get more “information,” and not prioritize any one “perspective.” As a result, a number of senior teachers failed to give appropriate support not only to the student but to the entire community and even discouraged many in the community from giving her appropriate support. According to the survivor, the consultants “reinforced my isolation by guiding GBZC leadership to keep me “anonymous” (rather than allowing me to decide who to talk to, when and how, although I ended up doing that anyway). They further allowed my abuser and the community as a whole to process the situation without me. Yet at the same time they allowed my main source of support (the board and other leaders who did know my identity) to be under attack for not remaining in some perceived ‘neutrality’ as if ‘neutrality’ were fair in this case.” Having already been cut off from her support network for over a year by the teacher’s insistence that their relationship be kept secret, the consultants’ work largely increased her feeling of isolation and of being unheard.

- The process the consultants introduced also did not serve the true needs and interests of the teacher who abused. Someone who commits this kind of abuse needs time to come to terms with their actions, learning about the seeds in themselves that led to the abuse, and needs to be supported by trained professionals in an ongoing therapeutic relationship. The consultants’ process instead forced the transgressor to engage with others prematurely while still in a mode of crisis-oriented self-justification and self-defense. Not surprisingly, we observed the abuser turning to gaslighting and attacking others, thereby creating more content for remorse, if/when he comes to terms with the enormity of his misdeeds. Although the transgressor in our community advocated to work with RUP, we believe it was an enormous disservice to his own learning and recovery to be involved in this kind of process.

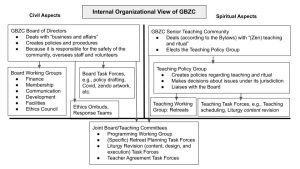

- The RUP consultants’ process attempted to sideline the sangha’s governing board. In seeming ignorance of the structure of nonprofit organizations, they told the board it should be “neutral” and encouraged the board to totally rely on them to address the situation. Instead of facilitating the healing of relationships within the sangha, this process created further divisions since those whose sympathies lay mainly with the teacher used the consultants’ advice to cast aspersions on, and sow distrust of, the elected board whenever it attempted to fulfill its “duty of care.”

GBZC, like many Buddhist communities, was pulled in by Right Use of Power’s promise of a spiritually informed approach to power. However, we’ve seen that the “spiritual” approach adopted by Right Use of Power during 2019-2021 was based on theories of power and responsibility that we found to be well outside mainstream consensus on how to frame these matters, the logical endpoint of their approach being victim-blaming. Cloaked in a rhetoric of compassion and forgiveness, their model enabled deflection by transgressors and led to further victim shaming. A rhetoric about forgiveness and compassion unaccompanied by meaningful justice-making and accountability resulted in complicity with the transgressor and their violation, and further harmed the victim, the community and the spiritual path.

Next: Sangha Responses to Misconduct: Rebuilding and Revisioning

First posted Oct. 3, 2022

Last revised Nov. 22, 2023